By Joseph Zappia, CIMA, CCO, Co-CIO

Deciding to do nothing is an active decision. Investors might be best served by resisting the urge to take action, and thereby resisting “action bias.”

A research study called, “Action Bias Among Elite Soccer Goalkeepers: The Case of Penalty Kicks,” explores the theory that soccer goalkeepers have the best chance of stopping a ball by standing in the middle of the goal and not making a dive toward either side. Penalty kicks are kicked 12 yards from the goal line at an average speed of approximately 60 mph. With the ball so close to the goal, the goalkeeper has almost no time to guess where the ball is going and to react correctly every time. The research found that when the goalkeeper stayed in the middle, he saved 33% of all kicks. When he dove left, he saved around 12.2% of the time and when he dove right, he saved around 12.8%. Even given these stats, the goal keeper still moves from the middle of the goal 94% of the time.

The challenge is humans have action bias. So when under pressure, human behavior takes over and people would rather be seen reacting in some way even though they know doing nothing could be the better option. This theory translates well to investing. Sometimes the best thing to do is stay the course, have confidence in the plan you have in place, and play the long game.

Timing when to sell and when to buy can be difficult and requires two correctly timed decisions. No one can accurately predict short-term market moves, and investors who sit on the sidelines risk losing out on periods of meaningful price appreciation that follow downturns. Every S&P 500 decline of 15% or more from 1929 through 2019, has been followed by a recovery. The average return in the first year after each of these declines was 54%1.

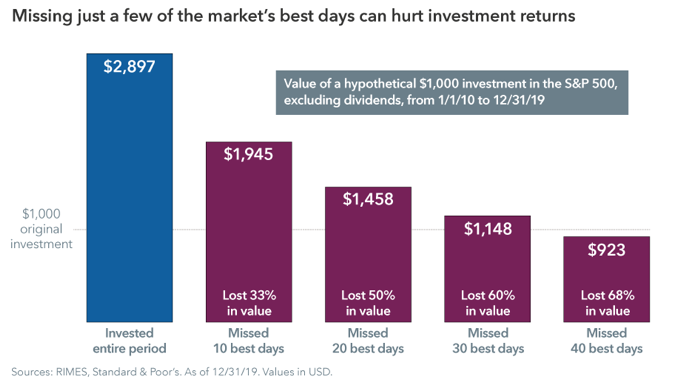

Even missing out on just a few trading days can take a toll. A hypothetical investment of $1,000 in the S&P 500 made in 2010 would have grown to more than $2,800 by the end of 2019. But if an investor missed just the 10 best trading days during that period, he or she would have ended up with 33% less.

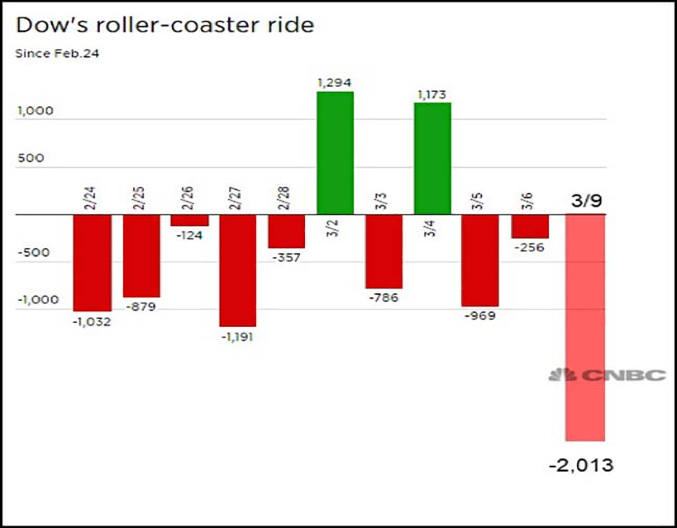

Missing the best days is tough enough–compound that with the fact that the best days typically occur within 14 days of the worst days – investors can get whip-sawed trying to time it. The market has been a roller-coaster ride since February 24, 2020.

Long-term investors should generally avoid selling on big down days. In fact, if you follow our stock market playbook, you’ll notice the best days often happen within a few days of the worst days. Adding capital on those days is seldom a bad idea if you are a long-term investor.

Source:

1 https://www.capitalgroup.com/advisor/insights/articles/handle-market-declines.html

Disclosure: The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investments may be appropriate for you, consult with your financial advisor. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.